Who Was the First European to Reach America? Another Contender

by Aiden Wetterhan, Form IV

4 min. read — March 24, 2022

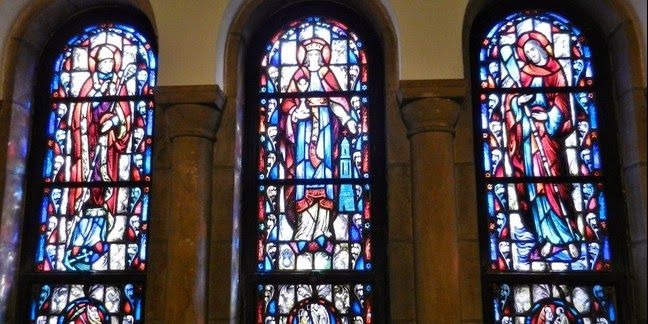

Many historians believe that Leif Erikson was the first European to reach the Americas, but one reasonable contender for that position could have reached the New World almost 500 years earlier. This man is an Irish monk who goes by the name of St. Brendan. Born in County Kerry in 484 AD, St. Brendan immediately entered the Catholic world. He received a Catholic education at a young age and was ordained by St. Eric in 512 AD. He was an excellent navigator and sailor, establishing monasteries on many islands surrounding Ireland. However, his greatest achievement was yet to come. St. Brendan and a group of monks set sail for the Garden of Eden. They began by fasting for 40 days, and then began their trek in a curragh, or skiff made of wood, hides, and tar. During this expedition he was said to encounter a sea monster, a river so wide that it was impossible to cross, demons who threw fire, and crystal pillars. At last he reached what he called the Fortunate Islands, or St. Brendan’s Island as it is called today, all before returning home. You might be wondering: how can this tale serve as a historical account? The Vikings, an American biologist, and a British navigator helped to turn this extravagant tale into a worthy record of possibly the first European to reach the Americas.

Many people have promoted the idea that St. Brendan reached the Americas. One saga from the Vikings describes a group of Native Americans who spoke a dialect similar to Irish. Still another saga tells of a group of Indians who had met white explorers dressed in white prior to the arrival of the Norse. Furthermore, the sagas speak of the Irish establishing monasteries on Iceland before the Norse had reached this land. Many Vikings at the time knew of the great navigational expertise of the Irish. More definitive proof comes from the American Biologist, Barry Fell, who found several petroglyphs, rock inscriptions, in West Virginia in 1983. These petroglyphs included Irish inscriptions from the 6th to 8th centuries along with Christian imagery. This evidence sounds too good to be true, and many scientists and historians agree, pointing to many flaws in Fell’s examination and historical analysis of the petroglyphs. On the other hand, the British navigator Tim Severin helped to disprove the belief that no man could travel in a curragh from Europe to America. Of course, the only reasonable thing to do in this case would be to travel in a curragh, following the supposéd route of St. Brendan from Ireland to Iceland to Greenland to Newfoundland. Severin accomplished this astonishing feat in a year compared to St. Brendan’s seven years. While this evidence certainly helps to bolster the tale of St. Brendan to a possible historical account, none of it proves that St. Brendan indeed made it to America.

When evaluating the validity of the claim that St. Brendan was the first European to reach the Americas, one must consider the basic details of St. Brendan’s life, the source of the story of his voyage, and if the other preponderances are affirmed. Lastly, one must still question if the legendary St. Brendan’s island is indeed in the New World. History can safely affirm that St. Brendan did exist and that he was an excellent sailor who established many monasteries in the name of the Holy Trinity. Furthermore, several important dates in his life are well-accepted. However, the source of St. Brendan’s journey to the Fortunate Islands are where the first issues arise. This journey is described in the 9th century book Navigatio Sancti Brendani – The Voyage of St. Brendan. This book was written in the immram literary genre, in which a navigator sets sail to distant islands, meets spectacular creatures, and returns home. This does not necessarily take away from the credibility of the source, but its religious style and fantasy depictions warrant a great deal of skepticism. During this time period, it is not uncommon for a book to be written about an event for the first time, several centuries after it has occurred. Furthermore, earlier books could have been written about St. Brendan that are yet to be found. If historians can get over these questionable details, there is still the issue of where St. Brendan’s island is located. Some speculate it is a part of the Azores, Canary Islands, or even near the equator. However, the description of demons who throw fire and crystal pillars could refer to the geography of Iceland i.e. volcanoes and glaciers, respectively, hinting at least towards the potential direction of St. Brendan’s voyage. Though the evidence for St. Brendan’s title of “the first European to reach the New World” borders on mere speculation, it behooves historians and academics to look at long-believed ideas with a healthy dose of skepticism in pursuit of the truth. In this instance there is the possibility that the link between the New and Old World dated back to only 150 years after the fall of the Roman Empire.